How Ivy’s Level 4 Government Funded Home Care Package is a lifeline

As seen on SBS News

How does a Level 4 Home Care Package benefit Ivy?

- Ivy is not suited to living in a nursing home, she’s too fit.

- Ivy loves walking and seeing the flowers, birds and sky. Staying at home means Ivy can go for long walks with her carer at a time that suits her

- Staying at home allows Ivy to feel safe all day in her familiar environment

Ivy Anderson (nee Chaulk)

From Indigenous Childhood to Western Womanhood

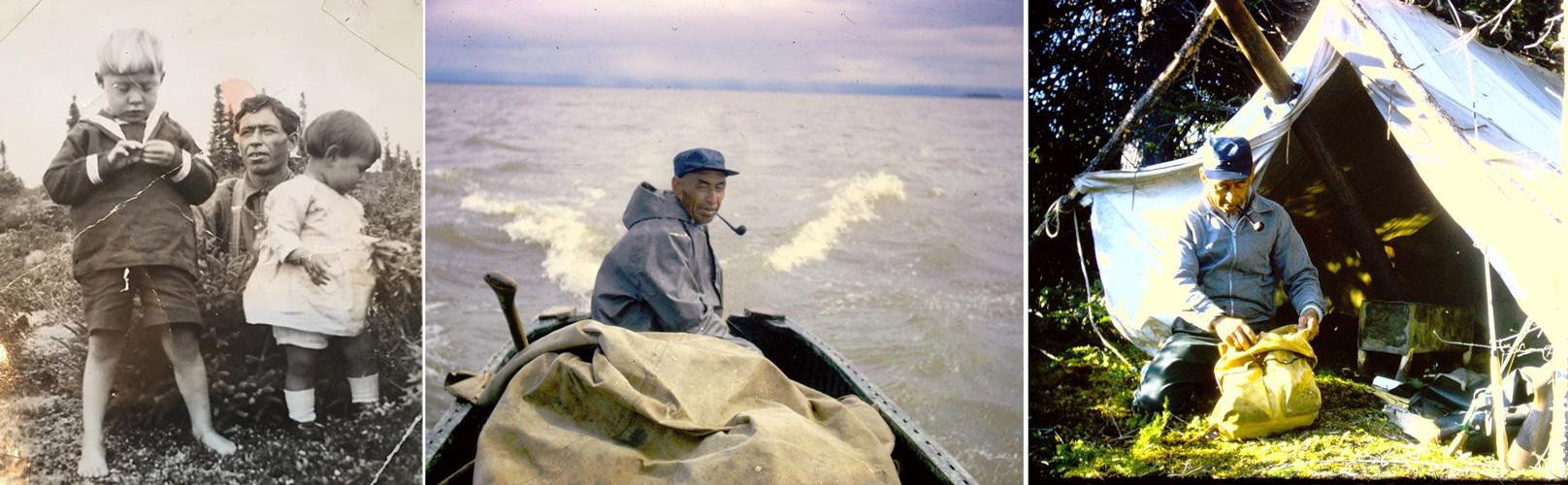

Ivy was born in a remote area of Labrador, called Pearl River, in North Canada, in 1932; the middle child of an indigenous family, with an older and younger brother.

At the time only two families lived there, such was its remoteness. Ivy’s dad, Percy, was a Trapper, Hunter and Fisherman, and both families lived off the land with little contact from the outside world.

The only currency they had were furs, which they traded at the North West River Trading Post.

Ivy’s geneology is part Inuit and includes 15% Native American DNA with a mixture of English and Scottish from the early settlers who were Basque Whalers from France and Spain, during the 16th century. Evidence of their presence has been found in Red Bay, Labrador, a haven 400 miles north of St. John’s.

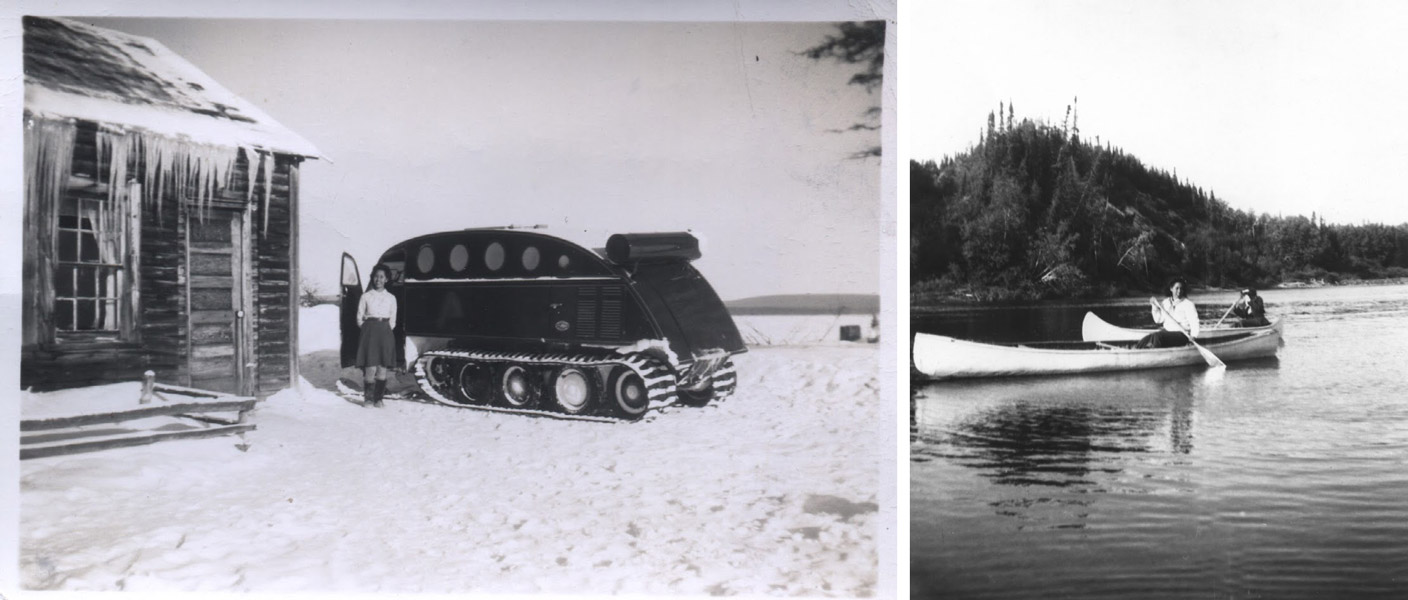

North West River Trading Post

North West River is a small town located in Central Labrador. It was established in 1743 as a trading post by French Fur Trader Louis Fornel. The community later went on to become a hub for the Hudson’s Bay Company and home to a hospital and school, serving the needs of coastal Labrador. North West River is the oldest modern settlement in Labrador.

When the children of the remote families reached school age, they moved to North West River to attend the ‘one room’ school. The school teacher at the time lived with them, which Ivy, as a young girl, was not very happy about. Ivy’s youngest brother, George, still lives in that original house.

After completing her primary school education, Ivy worked in the Hudson Bay Trading Store at North West River (which is now a museum).

Ivy Ice Skated 35 kms to Work

Goose Bay was 35 kilometres from North West River, Ivy’s home, so she lived in the barracks during the week, and during the winter months Ivy ice skated the 35 kilometres, each weekend, to and from home, to spend time with her family.

Ivy at Mulligan near Goose Bay

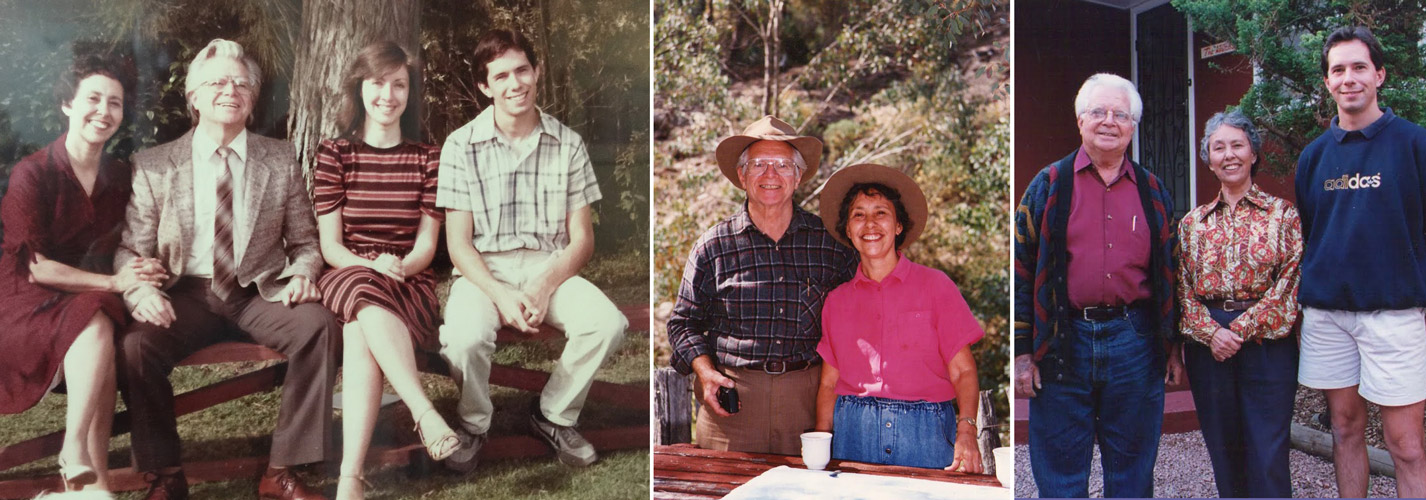

It was at the Military Base that Ivy met Kelvin. Kelvin was the only Australian living on the base amongst some 12,000 military personnel and their family. Kelvin was born in 1930 in N.Z. however moved with his family to Australia in the mid 1930’s. As a young man he worked as a Merchant Seaman, travelling the world’s oceans, ending up in North America in the early 1950’s. In addition to the ocean and traveling, Kelvin also loved Electronics and so he worked in maintenance on the Military Base.

Not long after they met at the base, Kelvin received an opportunity to work for a multi-national company, in Toronto, as an Electrical Engineer. The company was becoming a major player in the newly developing plastics industry. It seemed like the brief encounter between Ivy and Kelvin had come to an end.

And then fate lent a hand

Not long after Kelvin left Goose Bay, Ivy also received an opportunity in Toronto. The Grenfell Mission sponsored Ivy to attend Secretarial Studies at a Ladies College in Toronto. Ivy wrote to Kelvin and he picked her up from the airport.

As the story goes, when driving from the airport to her accommodation, Kelvin would naturally stop at the red traffic lights. After this happened a couple of times, Ivy asked him “why do you keep stopping?” Ivy had never seen traffic lights having lived in the remoteness of the Labrador Canadian landscape. Ivy’s time in Toronto became life changing, as Kelvin and Ivy married in the mid 1950’s.

Marriage and Children

Over the next six years, they had two children, Carolyn in 1958 and Keith in 1961. And then in 1963, Kelvin received a major promotion, which required him to move to the company’s Research Centre in South Carolina. He and Ivy decided to purchase a 60-acre farm in this beautiful rural area, which was only 30 minutes travel to Kelvin’s office. During their holidays, the family travelled back to Labrador to see Ivy’s parents.

From living on remote ice to living on water in New York

Within a few more years, Kelvin’s career was skyrocketing, and he was asked to move to New York City. Once more Ivy and her family were on the move. They sold their farm and, due to Kelvin’s love of boats, they purchased a 100-foot yacht, which they lived on in New York Harbour.

So, here was Ivy, a woman who had grown up as an indigenous child in one of the remotest, coldest regions on the planet; a place where only two families lived, and she was now living, as a western woman, in New York, the largest city in the world at the time.

Ivy adapted extremely well to New York city life, due to her very sociable nature and the fact that people warmed to her immediately. Additionally, Ivy had learnt, growing up with her Indigenous Elders, what resilience truly means and how to accept each new reality.

“You all know that I have been sustained throughout my life by three saving graces – my family, my friends, and a faith in the power of resilience and hope. These graces have carried me through difficult times, and they have brought more joy to the good times than I ever could have imagined.” – Elizabeth Edwards

Nature’s Child – Wild, Free and Adventurous

Ivy was an extremely active and energetic youngster growing up, and just loved being in nature. Remember she had spent most of her early life walking, running and ice skating in Labrador’s many extreme seasons.

Ivy also embodied the connection to the land and animals. Growing up in such arctic remoteness, her family’s lives were dependant on their team of huskies and she was closely connected to the dogs.

Such was her father’s reverence for his huskies, he never stood on the sled, thereby avoiding putting his own weight as a load on them – instead he would run alongside. This is how Ivy grew up. Wild, free, considerate and adventurous.

Ivy came from a long line of fur hunters and trappers, whose resilience in extreme and often dangerous conditions is the stuff of legends. They were also sustainable hunters who had their own areas which other hunters respected. Given the solitary isolation of these men, they were often out for four to five months at a time, in the wilderness, on their own. If they hurt themselves, they had no way of contacting anyone for help.

They also had no idea what was happening at home with their families, who had to survive without them. Ivy’s mother, Esther, was the eldest of six children. When Esther was 14, and her dad was away fur hunting, her mother, Drucilla, died during childbirth. Not only did Esther have to look after her siblings until her father returned, she also had the job of burying her mother, and telling her dad that his wife had died.

This is where the mental strength and emotional resilience of these amazing indigenous women was developed and handed down to their own children, especially their female children.

Likewise, children died from medical conditions such as appendicitis or whooping cough. Ivy’s mother was suspicious when strangers came through the region and visited. She’d heard that Smallpox was around, so she boiled up everything these visitors had used, from clothes to plates, pots and other utensils. Other people in the region died of smallpox, however none of Ivy’s family did.

This was the lineage of women, and men, that Ivy was born and bred from. Strength was in her genes and being inactive was never an option. Nor has staying in one spot for long.

Australia here we come

In 1971 Ivy’s life was about to change once more. Kelvin by now held a very senior and prestigious role in the company he had been working in for many years. The job however had begun to take its toll on him, and his parents back in Australia were getting older. This was also the time of the Vietnam War and racial unrest in America. Riots were escalating over the growing civil rights movement and riot police were using teargas to control the crowds. Both Kelvin and Ivy wanted their children to grow up in the relative peace and safety of Australia.

Life however was not going to be to kind to them on their arrival in Australia. Back in the 1950’s, Kelvin had hurt his back, and was put on Cortisone, considered to be the new wonder drug at the time. It wasn’t known back then the potential side effects which can include permanent damage to the glandular system and bone depletion leading to osteoporosis.

Ivy becomes the Family Breadwinner

On their return to Australia, Kelvin spent several years in and out of hospital, so Ivy became the family breadwinner, gaining a position as a Doctor’s Receptionist. She held this position for more than 20 years, working well into her 60’s, and to this day, patients still recognise Ivy and say hello when they see her in the street.

2016 Final Visit Back Home

In 2016 Ivy travelled back to Canada to see family and friends, and to re-visit the world of her youth.

Ivy is still living in the family home they purchased in Hornsby in 1973. Her beloved Kelvin however passed away in 2010, and the shock of losing not just her husband, but her soul mate, her adventurous friend in life, began a slow, and at first unnoticed deterioration in Ivy.

In 2017 Ivy was formally diagnosed with a dementia. The Doctor told her family she must have had it for at least three years. Daughterly Care was called in and they now provide ongoing, in-home care for Ivy, with Suki, a Daughterly Care Caregiver who was born in India, and moved to Australia in 2008. Suki, short for Sukhjeet, has become an extended and integral part of Ivy’s family, allowing Ivy to maintain her freedom and her dignity.

Walking is Ivy’s breath of life

All throughout Ivy’s life, being active and walking has been, and continues to be, Ivy’s favoured state of being. It is her natural stress release and therefore her energy vitaliser. Her journey from indigenous child to western woman, has sustained her love for walking and being in nature through to this day.

Ivy is now in the middle stages of Dementia, and it is becoming more difficult for her family to hold a meaningful conversation with her. What has not changed though is Ivy’s absolute inherent need to keep walking, to keep being in nature. Ivy told Daughterly Care’s CEO, “When I walk I see the flowers, the trees, and the blue sky”. Whether it is raking up leaves in her back yard or going for a daily walk with Suki. Walking in nature is Ivy’s breath of life, her sustenance.

Ivy was born free in the remote, natural wilderness on the other side of our planet…and as long as she continues her daily walks…then somewhere within her being, Ivy feels free!!

“When you truly sing, you sing yourself free. When you truly dance, you dance yourself free.

When you walk in the mountains or swim in the sea, again, you set yourself free.” Jay Woodman